Dispossessed on Their Own Lands Occupied by Canada: Tackling the Crisis of Indigenous Houselessness

The disconnect between the acknowledged sovereignty of Indigenous peoples on the land we now call Canada and the harsh reality of their houselessness is deeply embedded in the historical fabric of the genocidal country we all live in. The inception of treaties, such as the *Numbered Treaties, was meant to honour the sovereign rights of Indigenous peoples across the expanse of *Turtle Island. Yet, the legacy that followed has been marred by a narrative of forced removal and loss. The Indian Act of 1876 and its subsequent amendments exemplify the legislative tactics that have gradually undermined Indigenous autonomy and prompted a widespread estrangement from ancestral lands. This act, far from being merely regulatory, has actively paved the way for the current housing crisis afflicting Indigenous communities—a crisis that continues to intensify with each passing year.

Socio-Economic Impacts and Systemic Marginalization

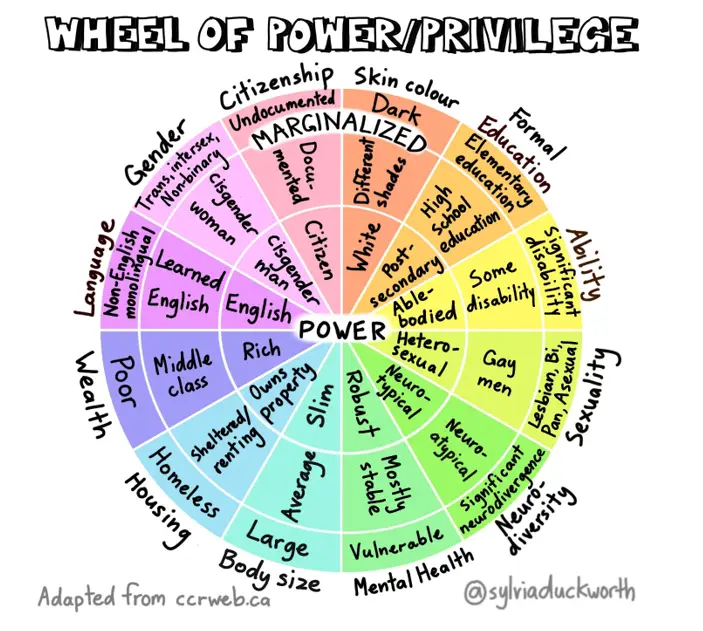

The susceptibility of Indigenous peoples to houselessness is inextricably linked to the pervasive socio-economic inequities rooted in colonialism that continue to afflict Indigenous communities by way of municipal laws, provincial laws and federal laws. Indigenous peoples who are houseless face a constellation of barriers, including disproportionate levels of poverty, unemployment, and obstacles to education. These systemic inequities are not incidental but are the direct result of colonial policies each system in Canada secures and upholds. Consequently, many Indigenous individuals are precariously perched on the edge of houselessness, a state exacerbated by enduring colonial mechanisms operating without genuine accountability and mired in performative excuses like, ‘I don’t know how to decolonize’.

Policy Failures

The Canadian government’s oversight in fully embracing and implementing the country’s inherently multi-juridical structure—comprising common law, civil law, and crucially, Indigenous law—has been a considerable factor in exacerbating the crisis of Indigenous houselessness. Policy-making processes have blatantly ignored Indigenous ways of being, and have always remained willfully blind when it comes to engaging with Indigenous nations meaningfully, thereby sidestepping legal and contractual obligations through the treaty, as well as inherent rights. This systemic exclusion and disregard, a contemporary reflection of colonial attitudes, has given rise to a renewed form of colonization and social injustice. It manifests in the sprawling ‘tent cities’ that have become all too common, serving as stark reminders of disparity as they stand in the shadows along our routes to work.

Legal and Human Rights Considerations

The Indigenous houselessness crisis transcends mere policy concerns, encapsulating significant legal and human rights issues. Canada’s ratification of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples signifies a pledge to safeguard Indigenous rights, encompassing the right to adequate housing and the maintenance of their unique political, legal, and cultural institutions. Nonetheless, the federal, provincial and municipal governments ongoing failure to effectively address Indigenous houselessness not only breaches these committed rights but also calls for an urgent overhaul of strategies. Such a shift must harmonize domestic actions with international human rights obligations, ensuring that the rights of Indigenous peoples are not only recognized but actively protected and fulfilled.

Implications for Canadian Society

The pervasive issue of houselessness among Indigenous peoples in Canada not only reveals the depth of societal divides but also calls for a significant paradigm shift in societal thinking and problem-solving approaches. The growing visibility of ‘tent cities’ and widespread homelessness is a stark indicator of these divisions. To effectively address these challenges, Canadian society must transition from an individualistic mindset to one that embraces Indigenous wholistic perspectives. This shift is crucial as solutions rooted in colonial individualism have proven inadequate in bridging the gaps. Embracing Indigenous ways of knowing, which emphasize community, interconnectedness, and collective well-being, could offer more sustainable and inclusive solutions to these deeply entrenched societal issues. This approach requires a fundamental reevaluation of values and strategies, moving towards a framework that not only acknowledges but actively incorporates Indigenous wisdom in shaping a more cohesive and just society.

Conclusion

The crisis of Indigenous houselessness in Canada underscores a striking inconsistency: whereby Indigenous peoples, who are one with the land, now disproportionately find themselves without shelter on it. This circumstance, deeply enmeshed with the country’s colonial past, calls for a unified approach from government, policymakers, and civil society to foster meaningful transformation. The solution requires more than just housing provision; it demands a deep respect for the sovereignty, inherent rights, and laws of Indigenous peoples. The road ahead must be forged with authentic reconciliation, respect, and a dedication to amending historical and ongoing injustices. Only through such a decolonizing approach can federal, provincial, and municipal governments begin to address this severe disparity—where those intrinsically connected to the land are left without a place on it—and move towards a future that respects the original laws of the land and the Indigenous peoples who sustain and live by them.

References

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report.

UN General Assembly. (2007). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. United Nations.

*Footnotes

*The Numbered Treaties are a series of eleven treaties signed between the Crown and Indigenous nations from 1871 to 1921. These treaties were created to establish guidelines for the relationship between First Nations and the Crown primarily concerning land rights and entitlements.

*Turtle Island is a term embraced by some Indigenous cultures in North America to denote the North American continent. In this post, I am referencing Turtle Island in what we currently call Canada today. Turtle Island finds its roots in Indigenous Creation Stories, where the landmass is metaphorically depicted as resting atop a colossal turtle, symbolizing a deep connection to nature, the spirit, the animals, humans, and the earth.