A Call to Action: Overcoming Linguistic Barriers and Oppression Towards Indigenous Peoples in the Justice System

In Canada, Indigenous people face significant challenges when interacting with the justice system, including linguistic barriers. Unfortunately, there are numerous stories of police officers and lawyers who assume that an Indigenous person who speaks with an accent is drunk. These individuals wield ultimate power and authority in their positions, and their lack of understanding that Indigenous Peoples can know more than one language, including complex Indigenous languages that may be unfamiliar to delicate colonial ears, can wreak havoc in someone’s life. Such assumptions represent a significant failure in the Canadian education system and highlight the widespread racism and bias that assumes someone is drunk instead of recognizing their different linguistic background.

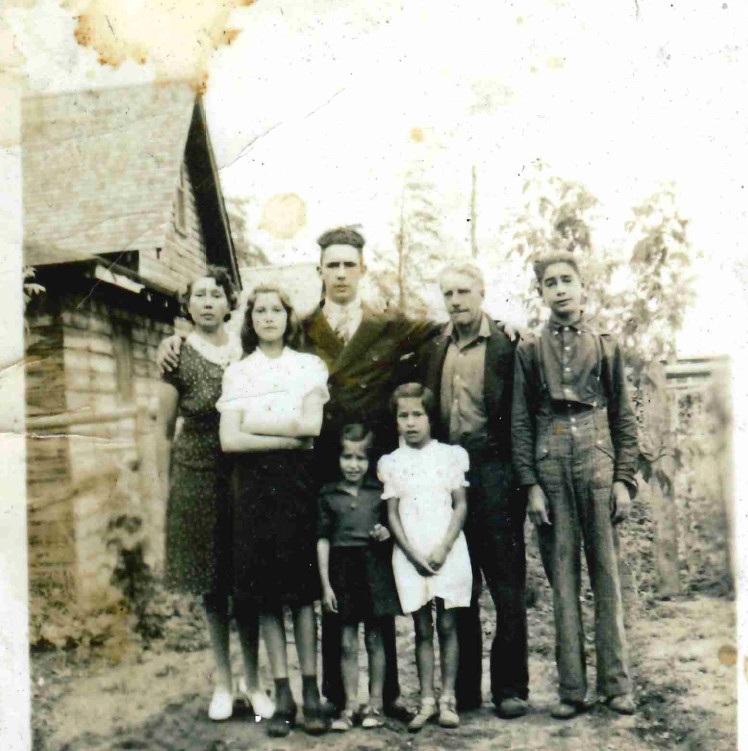

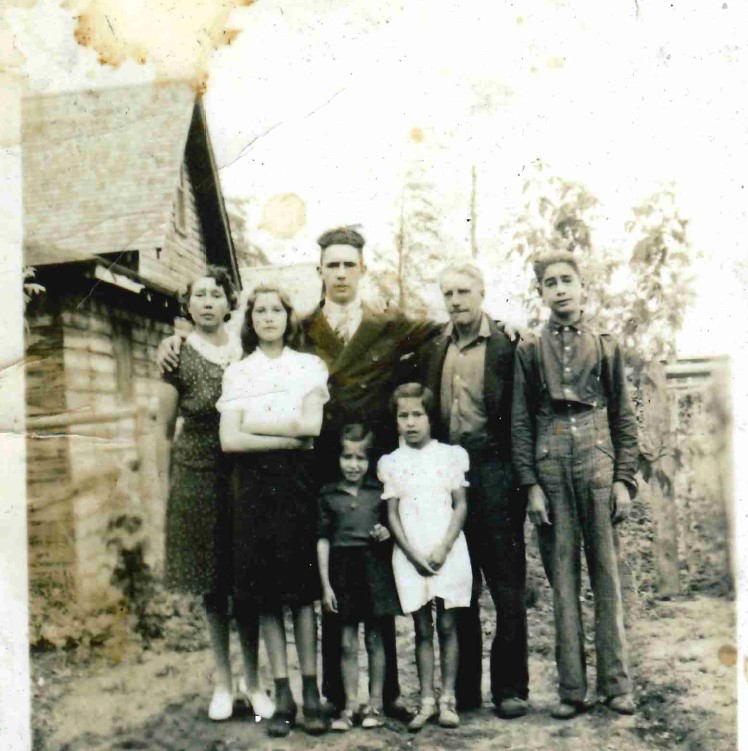

My own great grandmother, who was Métis, was fluent in five languages, including Ojibwe, Cree, English, French, and Michif. Unfortunately, she faced discrimination in her small town, where my Métis family spoke French as their first language due to racism. My great grandmother was forced to hide her Métis identity and pass herself off as French, which highlights the depth of systemic racism that has been pervasive in Canada’s history.

Indigenous languages were the first languages spoken in Canada, with over 70 Indigenous languages recognized in the country. These languages can be classified into 12 language families, such as Algonquian, Inuit, Athabaskan, Siouan, Salish, Tsimshian, Wakashan, Iroquoian, Michif, Tlingit, Kutenai, and Haida. Cree, Inuktitut, Ojibway, and Mi’kmaq are among the most widely spoken Indigenous languages in Canada.

Recently, the Canadian government recognized the importance of Indigenous languages and took steps to support revitalization, preservation, and promotion of Indigenous languages through the Indigenous Languages Act that was passed in 2019 to ensure that Indigenous languages are recognized as official languages of Canada alongside English and French. The Act also acknowledges that Indigenous languages were the first languages spoken on the land that is now Canada and that they have been historically and systemically suppressed through colonization and other forms of oppression.

At the heart of any language or dialect is a complex system of sounds, words, and grammar that allows us to communicate with one another. These components work together to create a rich and nuanced system of communication that is capable of expressing a vast range of different ideas and emotions. The sound system, or phonetics, is responsible for the unique set of consonants and vowels that make up a language’s distinct sound. The grammar consists of the rules and patterns that govern how words are used and arranged to create meaning. Finally, discourse styles encompass a wide range of non-verbal cues and communication strategies that are used to convey meaning, including intonation, pauses, bodily and facial gestures, and eye contact.

Aboriginal English

In my “Reconciliation and Lawyers” course, I use the “Communicating Effectively with Indigenous Clients” guide produced by Aboriginal Legal Services. The guide, written by Dr. Lorna Fadden, a Métis linguistics expert who earned a PhD in 2008 and now practices law, focuses on the importance of language in legal proceedings and how linguistic prejudice can disadvantage Indigenous clients. Part II of the guide emphasizes the differences between Standard English (SE) and Aboriginal English (AE), which encompasses a range of dialects spoken by Indigenous communities. These dialects share many features and differ from SE in pronunciation, grammar, and discourse style.

The guide provides examples of the prejudice that arises from speaking AE. For example, police officers have mistaken pronunciation differences for slurred speech and locked up Indigenous people for being drunk. Elders have been denied medical care because emergency room staff assumed intoxication rather than stroke or seizure, and children have been over-diagnosed with pathological speech disorders and prescribed unnecessary speech therapy when they speak the language of their community. These examples illustrate the on-going institutionalization of Indigenous people in Canada, in part due to linguistic prejudice.

AE is not a single variety of English. Rather, it’s a “catch-all phrase” for a range of dialects spoken by many in Indigenous communities, rural and urban alike. Across Canada, many Indigenous Peoples use similar varieties of English to construct an Indigenous identity. Sometimes called “Indian English” or a “Rez accent”, these varieties share many features. AE for example is characterized by different pronunciations and slightly different grammar. Similarly, there is no “true” English, rather SE is a collection of dialects that (for example) English Canadians can speak from coast to coast with variations in pronunciation, grammar and discourse style.

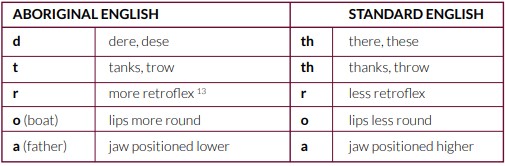

Phonetics Examples Between Aboriginal English and Standard English

In the study of linguistics, one of the sub-disciplines is phonetics which focuses on the sounds of speech. Unlike SE, AE is more complex due to the wide range of Indigenous languages spoken across Canada. The phonetic characteristics of AE vary depending on the influence of Indigenous languages on a particular dialect. However, some phonetic features are common to many dialects of AE, these include:

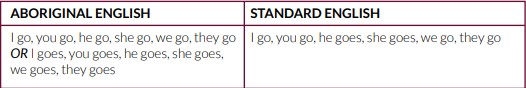

Verb Endings Between Aboriginal English and Standard English

When it comes to verb endings, there are some notable differences, for example:

I can continue with going further with explaining: prounouns, double and triple negatives, intonations, pauses, speech rate, eye contact, and how much or how little is said. But you can find it in the guide.

What You Can Do For Your Client

In court, you can inform judges and other legal professionals of the linguistic differences that exist in AE to avoid any linguistic prejudice or misunderstandings. Furthermore, different discourse behaviors may not indicate uncooperative or evasive behavior (for example, eye contact) so it’s important to check your own biases and approach communications with Indigenous Peoples with an open and flexible mind.

For evidence gathered through police interviews, it’s important to be aware of the possibility of cross-linguistic miscommunication. Building trust with Indigenous Peoples may take time and requires a genuine effort to establish respect, but it’s incumbent upon you to represent Indigenous Peoples, Nations and communities with the highest integrity, competency and diligence you possess, above and beyond what the colonial profession expects from you.

In summary, the recognition and revitalization of Indigenous languages are crucial for reconciliation in Canada, as highlighted by the recent Act. However, we should not stop there. Linguistic barriers persist in the legal system, and there is much work to be done to overcome the systemic discrimination, structural racism, colonialism, and prejudice that continue to impact Indigenous Peoples and their lives through oppression, unchecked bias, and ignorance of linguistic differences between SE and AE. The “Communicating Effectively with Indigenous Clients” guide is an essential resource for legal professionals seeking to build respectful, reciprocal, relational, and responsible relationships with Indigenous Peoples, communities, and Nations, and provides concrete approaches you can work on to further reconciliation actions.